How To Make A Camera Trap Grid In Arcmap

Abstruse

Information from camera traps is used for inferences on species presence, richness, abundance, demography, and activeness. Photographic camera trap placement pattern is likely to influence these parameter estimates. Herein nosotros simultaneously generate and compare estimates obtained from camera traps (a) placed to optimize large carnivore captures and (b) random placement, to infer accuracy and biases for parameter estimates. Both setups recorded 25 species when aforementioned number of trail and random cameras (n = 31) were compared. However, species aggregating rate was faster with trail cameras. Relative affluence indices (RAI) from random cameras surrogated affluence estimated from capture-mark-recapture and altitude sampling, while RAI were biased higher for carnivores from trail cameras. Group size of wild-ungulates obtained from both photographic camera setups were comparable. Random cameras detected nocturnal activities of wild ungulates in contrast to generally diurnal activities observed from trail cameras. Our results show that trail and random camera setup requite similar estimates of species richness and grouping size, but differ for estimates of relative abundance and activeness patterns. Therefore, inferences made from each of these camera trap designs on the to a higher place parameters need to exist viewed within this context.

Introduction

Reliable estimation of species richness, abundance, action and subsequent monitoring play a pivotal role in achieving specific conservation goals through prove-based direction1. However, selection of suitable techniques requires a-priori assessment of their accurateness, precision, replicability, and price-effectiveness to meet the desired objectives before the technique is recommended on a large calibration. Camera traps have been widely used as a wildlife monitoring tool due to their objectivity, ease of apply, and power to generate information on a large spectrum of speciestwo. Camera trapping surveys are primarily designed to document species richness3, occupancy4, affluence indices5,half dozen, estimate abundance of individually identifiable species in capture-recapture frameworkseven,8,9,ten and make up one's mind their activeness patterns11. However, with the technological advances, researchers started using photographic camera traps to report population environmental12, camera trap-based altitude sampling13, behaviorxiv, forest ecology15 and carrying out conservation assessments16.

A basic supposition of all inferences from camera trap studies is that the information generated are unbiased representation of underlying parameters (of species richness, abundance, temporal activeness, either after correcting for effortseven and/or detection9,17). However, a typical capture-recapture written report is designed to maximize detections of the target species and is substantially non-random and ofttimes not systematic18. Such camera trap designs also generate secondary data on several non-target species which are oft used to infer their relative abundance indices19,twenty,21, activity patterns22,23, and occupancy estimates24. However, these inferences on the not-target species can be biased due to the sampling pattern and camera placement. Due to differential use of trails by different species25, biases can occur in estimating relative abundance, group size, and temporal activity21. In a review of 266 camera trap studies, Burton et al.eighteen plant 47.6% of studies using the same surveys to estimate variables of non-target species e.1000. occupancy, relative affluence, and activeness blueprint. Attempts to evaluate if such designs result in a biased inference and of what magnitude accept been few26,27,28,29,30. Di Bittetti et al.26 and Blake and Mosquera27 have summarized that a combination of trail and off-trail cameras volition provide a comprehensive motion picture of species composition and their relative abundance. While citing the higher up-mentioned approach Cusack et al.28, Wearn et al.31 and Kolowski et al.29 described difficulties in selecting the proportion and spatial distribution of these trail and random locations in a systematic sampling blueprint. Thus, they recommended the use of random camera setup and emphasized its importance in sampling microhabitats. However, they also showed that in order to eliminate biases in inferences made at the community level and overcome lower capture rates from random design, a large sampling effort would be required.

Herein, we deployed camera traps on trails to maximize photo-captures of tigers (Panthera tigris) and leopards (Panthera pardus) (trail cameras), and sampled simultaneously the same extent with randomly placed photographic camera traps (random cameras). We computed the rate of species accumulation, species richness, relative abundance, detection probability, group size and daily activity pattern of large and medium sized terrestrial mammals using both photographic camera placements and compared their outcomes. We besides calculated density estimates of ungulates from distance sampling and of tiger and leopards from spatially explicit capture-marker-recapture and regressed them against RAI values obtained from trail and random cameras. This experimental setup permits usa to test if photographic camera trap placement is an important aspect to be considered for estimating species richness, affluence, and action.

Methods

Study area

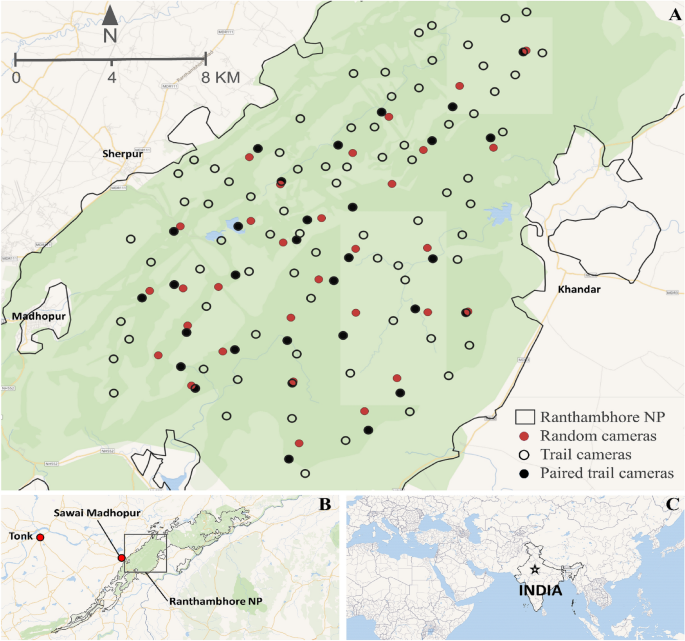

The study was carried out in Ranthambhore National Park, (76.23 Eastward to 76.39 E and 25.84 N to 26.12 N) situated in the semi-arid part of western Republic of india. The terrain is rugged and hilly, interspersed with valleys and plateaus which makes for largely 2 types of habitat i.east. woodland and savannahs. The area is dominated with tropical dry deciduous wood (dominated with Anogeissus pendula) and scrubland-thorn forests (dominated with Grewia flavescens, Capparis sepiaria). Ranthambhore experiences sub-tropical dry climate with hot and dry summer (March–June), moderately wet monsoon (July–September) and dry winter (October–February). A small solitary stream forth with homo-fabricated lakes and water holes manages to sustain the faunal assemblage of the park through the dry months. The flagship species of Ranthambhore National Park is the tiger and information technology serves every bit the source population of tiger in the semi-barren mural of western Bharat32. Other large carnivores include leopard, striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena), and sloth bear (Melursus ursinus). Meso-carnivore social club comprised of jungle cat (Felis chaus), golden jackal (Canis aureus), caracal (Caracal caracal), desert true cat (Felis silvestris), rusty spotted cat (Prionailurus rubiginosus), play a trick on (Vulpes bengalensis), and dearest badger (Mellivora capensis). Small-scale carnivores include small Indian civet (Viverricula indica), Asian palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus), ruddy mongoose (Herpestes smithii), Indian grey mongoose (Herpestes edwardsii), and small-scale Indian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus). Herbivores includes spotted deer (Centrality axis), sambar (Rusa unicolor), blue bull (Boselaphus tragocamelus), Indian gazelle (Gazella bennettii), wild hog (Hog), gray langur (Presbytis entellus), rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), black-naped hare (Lepus nigricollis), Indian crested porcupine (Hystrix indica), and peafowl (Pavo cristatus). For species richness we also included squirrels, monitor lizards and birds (grouped into 2: ground dwelling and other birds) in our analysis. The National Park area of Ranthambhore is mostly inviolate, withal, in the peripheral areas herders often breach the purlieus wall and push their cattle within the Park for grazing. We therefore also recorded all domestic and feral livestock (cattle, buffalo, goats, camels, donkeys, and dogs) that were photo-captured.

Field method

Photographic camera trapping

The study surface area was divided into grids of 2 km2 for systematic deployment of camera traps for both the placements. Trail cameras were deployed targeting population estimation of tigers and leopards in a mark-recapture framework and were positioned at locations to maximize their photo-captures. Tigers and leopards mostly use forest roads, animal trails, dry river beds, and fire lines to patrol their territories and to commute33. After a reconnaissance survey for carnivore signs and usage, a pair of camera traps was deployed at the almost suitable locations inside each grid to photo-capture tigers and leopards (October to December 2018). Trail cameras (Cuddeback™, WI5411 USA) were deployed at 106 locations, and operated for 25 days constituting an effort of 3537 trap twenty-four hours (no. of cameras × no. of operational days). Cameras were tied to a pole/tree at the height of xxx–45 cm from the ground, and placed iii–5 g abroad from the eye of the trail to ensure total-torso capture of the target animals. The time delay betwixt successive pictures was kept as 'Fast equally Possible' mode (ane–2 southward delay), even so, at night the delay increased to 8–ten s depending on the bombardment conditions (which is required to recharge the white light flash).

For the random design, 31 infrared flash cameras (Reconyx® Hyperfire HC500, WI 54636USA) were placed at random locations with (centroids of the sampling grids) a fixed bearing to maintain a random field of view. The camera height was kept at 30–45 cm above ground. The 'No delay' setting of the camera allowed it to take sequent pictures without whatsoever lag. Random cameras were operated for forty days constituting an try of 1035 trap days, each photographic camera was visited afterward 5–7 days to check their ready, battery status and to download the data.

Analytical methods

Species richness and accumulation

Photographs obtained from both the camera trap setup were archived and manually segregated to species. Since the number of trail cameras far exceeded the number of random cameras, nosotros used only the estimates derived from paired cameras (one trail photographic camera per site paired with a proximate random camera, distance range 90–900 m, Fig. ane) for meaningful and unbiased comparisons. Thus the richness and accumulation comparison was carried out using the data generated from 31 trail and 31 random cameras. Number of each species photo-captured by trail and random cameras were recorded to summate species richness and accumulation. To compare species richness obtained from these two camera deployment designs, we generated sample-based species accumulation (richness) curve from incidence information34. Confidence intervals (95%) were computed based on unconditional variance following the method of Colwell et al.35, with 100 permutations. For both camera placement designs, species aggregating curves were computed based on the time taken to accumulate new species and accomplish an asymptote.

A. Locations of random and trail cameras placement within Ranthambhore National Park. The solid blackness circles correspond trail cameras placed in the proximity of random cameras, i.east., paired trail cameras. Inset: B. Study area extent in Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve (RTR); C. Location of RTR in India. The maps were created using QGIS (ver. 3.x, https://download.qgis.org).

Relative abundance alphabetize

A conscientious scrutiny of each private photo sequence was done to determine independent photograph-capture events. Successive photo-captures (< 30 min apart) of the aforementioned species were considered as one event wherever the individual photo-captured animal(due south) could not exist identified with certainty (on the basis of gender, historic period course, and unique body markings). We used all random (n = 31) and trail (n = 106) cameras to summate the Relative Abundance Alphabetize (RAI). In case of trail cameras, captures of the same individual at a location in both camera units were considered as a unmarried capture (identified by the time of captures). The sampling effort was the sum of the number of days each camera was operational throughout the session; in case of trail setup, operational days of a camera station (photographic camera station consists of ii photographic camera units facing each other on a trail) was considered for try adding. Species RAIs were calculated for trail and random cameras as the number of independent events of each species, divided by the full sampling endeavor of all the cameras multiplied past 100five,36 i.e. contained photo-capture events in 100 trap-nights.

Furthermore, we plotted robust density estimates of tigers and leopards obtained using spatially explicit marking recapture and ungulates obtained from line transect based distance sampling from Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve reported in37 confronting RAI values obtained from trail and random cameras. Since density estimates were cotemporaneous and from the same region, the scatter plot, scaling, and correlation between density estimates and RAI enabled us to evaluate the relationship between abundance and RAI and biases (if any) between different camera placements.

Detection probability

In gild to gauge detection probability of species, nosotros analyzed their presence /absence data within a multi-method occupancy framework38 where the two camera designs were taken as the 2 methods. For occupancy analysis, we used all the random (n = 31) and trail (n = 106) cameras as occupancy framework accounts for heterogeneous sampling try while estimating the detection probability. Our aim was not to estimate the occupancy of the species in the written report area, just to compare the detectability of the species by two camera trap placements. The sampling grids of 2 kmii were considered as the unit for occupancy assay. The multi-method occupancy framework incorporates—(i) a local occupancy parameter (θ) (representing the probability of a region in the firsthand vicinity of the camera is occupied), (ii) a site occupancy parameter (ψ) (describing the proportion of the sampling sites being occupied by the species during the study period), and (iii) detection probability (pdue south t, 's' sampling method and 't' occasion)38. Site-wise detection histories were made for each species using photograph-captures obtained from the camera traps of both the sampling designs. Detection probabilities (occupancy interpretation) were computed using the software PRESENCE39.

Activity pattern

Camera traps provide a non-invasive way to observe and quantify animate being action at the population level in a relatively cost-constructive style11. We used the time stamp metadata obtained from random (northward = 31) and trail (n = 106) cameras to compute the activity pattern of wild ungulates and their major predators in the study area using the 'overlap' package in R40. 'Overlap' fits a kernel density part which corresponds to the photo-capture rate of the species in a time interval. The expanse under the bend (derived from kernel density function) represents the proportion of fourth dimension the species was active. Frequency of camera trap images of a species in time reverberate the activity of the species41. We estimated the degree of overlap (Δ—Delta4) betwixt the wild ungulate activity recorded from random and trail cameras. Due to very few captures of carnivores in random cameras, we computed their activity simply from trail cameras.

Group size

We calculated the grouping size of wild ungulates from the camera trap photo-captures. Nosotros counted the number of individuals of a species in an paradigm and all images from the consecutive camera trap photos within x min to record grouping size. Any animal getting photograph-captured afterward an interval of 10 min from the final photo-capture of the same species was considered equally a fellow member of a different group. We differentiated different individuals of a grouping by their physical characteristics and body markings to the best of our ability. Finally, we compared the frequencies of different group sizes observed from random and trail camera setups.

Results

Species richness and aggregating

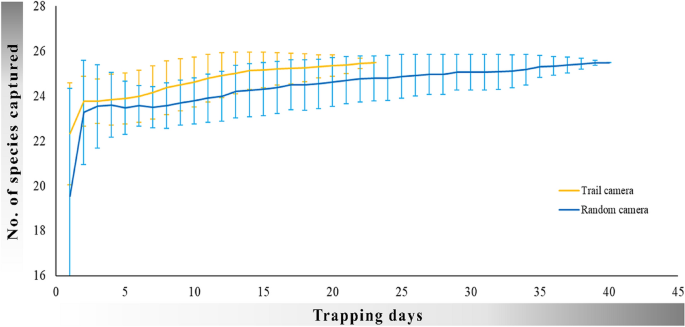

A total number of 32 species were photo-captured in trail cameras (n = 106), and 25 species were photo-captured in random cameras (north = 31) (Table 1). However, both random and paired trail cameras (n = 31, trail cameras placed in the proximity of random cameras) detected 25 species (equal species richness), out of which 23 were common for both setups (Supplementary Table 1). The rate of species accumulation for trail camera setup was college than that of random setup (Fig. 2).

Species accumulation curves from trail (yellow line) and random (blue line) photographic camera setups describing the rate at which species were captured in two setups. The vertical bars correspond 95% conviction intervals.

Relative abundance alphabetize

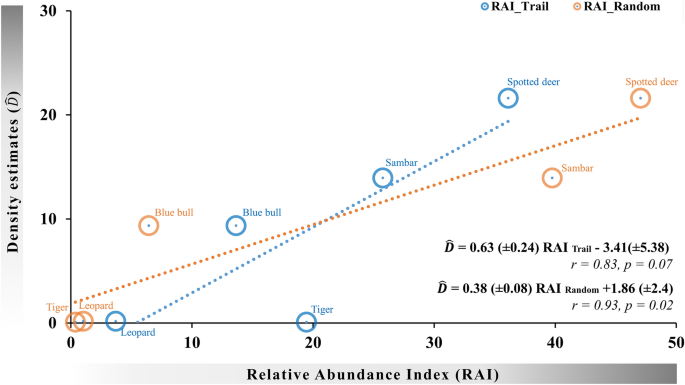

A total of 25,394 and 46,010 creature images were obtained from trail and random cameras, respectively. The relative abundance alphabetize (RAI) values of species obtained from random cameras were ordinated in the aforementioned order as absolute densities of these species while RAI of tigers and leopards from trail cameras were much higher than that from random cameras (Table 1, Fig. 3).

Scaling RAI values from unlike camera trap designs with accented density. Only RAI's from random camera trap placement designs had significant correlations with absolute density.

The RAI values obtained from random camera traps were highly correlated (r = 0.93, p < 0.05) with the density estimates obtained from SECR and distance sampling, while the RAI values from trail cameras were non significantly correlated (r = 0.38, p > 0.05) (Fig. 3) since tiger RAI was much higher. The linear equation depicting relationship betwixt density and RAI obtained from random camera was:

$$ Density \, = \, 0.38 \, \left( { \pm 0.08} \correct) \, RAI \, Random \, + ane.86 \, \left( { \pm 2.forty} \right) $$

Hither, a unit increase in density causes a 0.38-unit of measurement increment in RAI. The loftier correlation suggested that the relative abundance index obtained from random cameras can be used as a surrogate of abundance and also as an alphabetize to monitor trends in wild fauna populations.

Detection probability

Carnivore detection probability, obtained from occupancy estimation, was an society of magnitude college on trail cameras (Table 1). Information technology is noteworthy that herbivores detection probabilities in trail and random cameras were similar, whereas hare, porcupine, peafowl, and greyness langur had higher detection probabilities on trail cameras (Table i).

Action design

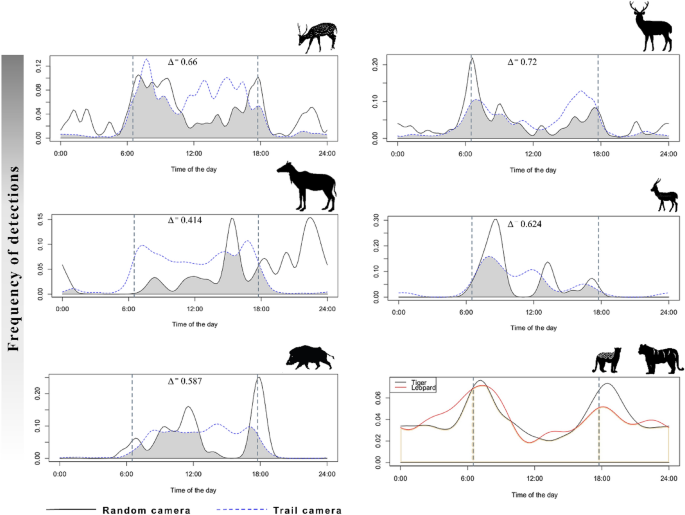

According to the trail camera photo-captures, spotted deer, blueish bull, wild squealer, and Indian gazelle showed predominantly diurnal action with very few captures at night, while sambar showed action peaks in the early morning and tardily afternoon hours (Fig. four). Contrastingly, data from random cameras showed spotted deer to take major activity peaks in the forenoon, with considerable photograph-captures in the evening every bit well as at nighttime. Sambar showed crepuscular activity peaks with night time activity in random cameras. The activity peaks for blue bull changed considerably in random cameras, where the species showed night fourth dimension peak in activity (Fig. 3). Tiger and leopard showed nocturnal activeness with crepuscular peaks from trail cameras; due to very less number of independent photo-captures in the random setup, we could not compute the temporal activeness from random cameras for these carnivores. The trail cameras detected a higher per centum of activities for all the ungulates, except spotted deer, than random cameras (Table 2). Overlap values of Δ between random and trail cameras were least for blue bull (0.41 maximum departure) and highest for sambar (0.72 highest similarity) (Fig. four) suggestive of substantial differences in estimates of percent time active between the two camera setups.

Activeness pattern of wild ungulates (L to R from summit: spotted deer, sambar, blue bull, Indian gazelle, and wild pig) and their major predators (tiger and leopards) in the study area. In each graph, the solid-black and dotted-blue line represents the species' activity pattern obtained from random and trail cameras, respectively; the grey shaded polygons depicted the overlap betwixt two curves. The vertical dotted gray line shows the timing of sunrise and dusk in the study expanse. Activeness pattern of tigers and leopard was computed merely from trail cameras.

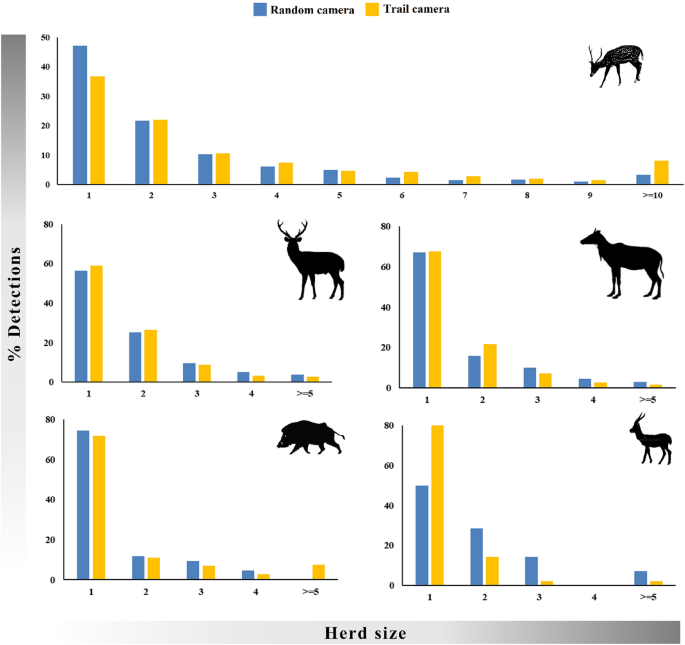

Group size

The average grouping sizes of all the ungulates obtained from both the camera setups were comparable, however, larger congregations were observed from trail cameras (Tabular array 2). The frequency of different group sizes observed in random and trail cameras were comparable for all wild ungulate species (Fig. v). Groups consisting of larger number of individuals were mutual in spotted deer, yet, for sambar, bluish bull, Indian gazelle, and wild pig single individuals were captured most frequently (Fig. 5).

Herd size of wild ungulates (Fifty to R from top: spotted deer, sambar, bluish bull, wild squealer, and Indian gazelle) recorded from the random and trail camera setups.

Discussion

Our results have implications on inferences of by studies and insights for planning future studies that utilise camera trap data to infer community composition, affluence, behavior and demographic parameter. Species accumulation curves deed as a baseline to amend the efficiency of hereafter customs surveys42, therefore information technology is important to enquire well-nigh the optimal sampling design for this purpose. Species assemblages recorded in random and paired camera setups were the same, however, the rate of species accumulation was faster in trail camera setup than the random camera trap setup (Fig. two). The above findings suggest that trail cameras placed for targeting large carnivore affluence estimation (in mark-recapture framework) can exist used to generate species inventories in a curt amount of time28.

Large carnivores, which occur at low density, patrol their territory using certain routes, were poorly captured in randomly placed photographic camera traps (Table 1). Thus, the abundance indices of large carnivores obtained from random cameras were lower than that of the trail cameras. Smaller carnivores, like their larger counterparts, were significantly less represented in the randomly placed cameras. Moreover, it seems reasonable that carnivores (with soft pads) adopt mud roads or animal trails over random walk in a mural with sharp pebbles and thorny vegetation. These findings were further endorsed by higher detection probability (Table1) (derived from multi-method occupancy analysis) of carnivores in trail cameras over the random cameras. Similar findings were published from the studies which constitute more carnivore captures on the trail compared to the off-trail and random cameras26,28. However, areas where man-managed road/trail densities are significantly low, studies did not discover whatever differences in captures between trail and not-trail cameras27. In our opinion, if the objective is to assess relative abundance of diverse species inside an ecosystem and compare these with density, then trail based RAI results are biased for large carnivores and random placement design results provide unbiased estimates of relative density (Fig. 3). Notwithstanding, if the objective of the study is to compare the relative abundance of the same species over time the use of trail-based photographic camera placement would likely provide more than precise estimates due to college capture probability and therefore be more useful in detecting population trends. Caution should be exercised while comparing population trends using RAI values obtained from trail cameras, equally detection rates tin can be influenced by camera placement, field expertise in choosing locations to maximize photograph-captures and animal movement rates at these not-random selected locations43. Thus, bias may non remain consistent over different sampling intervals when using RAI obtained from trail cameras.

Ungulate species did not show significant differences in photo-capture rates from trail and random cameras (Table one). Wild ungulates spend a big proportion of time foraging, and employ trails by and large while moving from one foraging patch to some other44. In consonance with our hypothesis, this explains the greater number of wild ungulate photo-captures in random cameras compared to trail cameras. While the average group size captured in both trail and random cameras were comparable, trail cameras recorded larger groups for ungulates (Table 2). This was likely as the species are known to motion in bigger herds while they carve up into smaller sub-groups for foraging to avoid competition45,46. Although detection probabilities of wild ungulates were similar from the trail and random cameras, their activity patterns were substantially different. Trail cameras captured exclusively diurnal activity for all wild ungulate species, while the random cameras showed a more realistic activity pattern with records of night-time activity for spotted deer, sambar, and blue bull (Fig. 3). Trails are extensively used past predators during nighttime, avoiding the use of trails at dark was likely an anti-predatory beliefs past wild ungulates47,48. Published activity patterns of these species have been obtained from trail cameras that focused on population estimation of large carnivores22,23 and therefore are probable biased towards diurnal activity.

Our study shows that both trail and random placement of cameras provide similar inference on species richness and composition, but trail cameras had faster accumulation rates and were therefore more cost-effective. Additionally, information on illegal activities inside the PA obtained from trail cameras were more comprehensive than random cameras. The relative abundance alphabetize (RAI) from both photographic camera designs was similar for wild ungulates but much lower for carnivores in random setup. Our results for RAI propose that random camera placement blueprint is unbiased for estimates of relative abundance of species within a community, only biased data from trail cameras could still be used for estimating trends in abundance over time for any species within the same geographical area of sampling. Opposite to our findings, a few studies take reported the superiority of random photographic camera setup over the trail-cameras for detecting rare species27,28, however, this was not the case for the semi-arid system that nosotros studied. Activity patterns of ungulates and proportion of time active significantly differed between random and trail cameras. We suggest that random cameras provide a more realistic representation of wild ungulate activeness while trail cameras are better suited for estimating activity of carnivores.

Finally, no single method tin address all the aspects concerning multiple species ecology or behavior, therefore camera trap surveys need to be tailor-made to cater to specific objectives49. Trail-based camera trapping is an important conservation tool for monitoring abundance of big carnivores that is required for their effective conservation. We show that ancillary data generated from this effort tin can additionally provide information on species richness, species specific trends in abundance and activity patterns of carnivores while inferences on activity patterns of ungulates from trail cameras can be biased.

Alter history

-

13 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41598-022-05223-w

References

-

Gese East. M. Monitoring of terrestrial carnivore populations. Carnivore Conservation. (2001).

-

Oconnell, A. F. et al. (eds) Camera Traps in Animal Ecology: Methods and Analyses (Springer Scientific discipline & Business organization Media, 2010).

-

Tobler, M. W., Carrillo-Percastegui, Due south. Eastward., Pitman, R. L., Mares, R. & Powell, G. An evaluation of camera traps for inventorying large-and medium-sized terrestrial rainforest mammals. Anim. Conserv. eleven(3), 169–178 (2008).

-

MacKenzie D. I., Nichols J. D., Royle J. A., Pollock One thousand. H., Bailey Fifty. A., Hines J. E. Occupancy Modeling and Estimation (2017).

-

Carbone, C. et al. The apply of photographic rates to estimate densities of tigers and other ambiguous mammals. Anim. Conserv. iv(i), 75–79 (2001).

-

Rowcliffe, J. One thousand., Field, J., Turvey, S. T. & Carbone, C. Estimating animal density using photographic camera traps without the need for private recognition. J. Appl. Ecol. 1, 1228–1236 (2008).

-

Karanth, K. U. Estimating tiger Panthera tigris populations from camera-trap data using capture-recapture models. Biol. Conserv. 71(3), 333–338 (1995).

-

Silverish, S. C. et al. The use of photographic camera traps for estimating jaguar Panthera onca affluence and density using capture/recapture analysis. Oryx 38(ii), 148–154 (2004).

-

Jhala, Y., Qureshi, Q. & Gopal, R. Can the abundance of tigers exist assessed from their signs?. J. Appl. Ecol. 48(1), fourteen–24 (2011).

-

Sollmann, R. et al. Improving density estimates for elusive carnivores: Accounting for sex-specific detection and movements using spatial capture-recapture models for jaguars in primal Brazil. Biol. Conserv. 144(three), 1017–1024 (2011).

-

Rowcliffe, J. One thousand., Kays, R., Kranstauber, B., Carbone, C. & Jansen, P. A. Quantifying levels of animal activity using photographic camera trap data. Methods Ecol. Evol. five(11), 1170–1179 (2014).

-

Roy, M. et al. Demystifying the Sundarban tiger: Novel application of conventional population interpretation methods in a unique ecosystem. Popul. Ecol. 58(1), 81–89 (2016).

-

Howe, E. J., Buckland, South. T., Després-Einspenner, M. L. & Kühl, H. S. Distance sampling with camera traps. Methods Ecol. Evol. viii(11), 1558–1565 (2017).

-

Bridges, A. South., Vaughan, M. R. & Klenzendorf, Southward. Seasonal variation in American blackness bear Ursus americanus activity patterns: Quantification via remote photography. Wildl. Biol. ten(1), 277–284 (2004).

-

Beck, H. & Terborgh, J. Groves versus isolates: How spatial aggregation of Astrocaryum murumuru palms affects seed removal. J. Trop. Ecol. 1, 275–288 (2002).

-

Kinnaird, Thou. F., Sanderson, E. W., O'Brien, T. One thousand., Wibisono, H. T. & Woolmer, Chiliad. Deforestation trends in a tropical landscape and implications for endangered large mammals. Conserv. Biol. 17(1), 245–257 (2003).

-

MacKenzie, D. I. et al. Estimating site occupancy rates when detection probabilities are less than one. Ecology 83(viii), 2248–2255 (2002).

-

Burton, A. C. et al. Wildlife photographic camera trapping: A review and recommendations for linking surveys to ecological processes. J. Appl. Ecol. 52(3), 675–685 (2015).

-

O'Brien, T. G., Kinnaird, M. F. & Wibisono, H. T. Crouching tigers, hidden prey: Sumatran tiger and prey populations in a tropical wood landscape. Anim. Conserv. 6(two), 131–139 (2003).

-

Datta, A., Anand, Yard. O. & Naniwadekar, R. Empty forests: Big carnivore and prey abundance in Namdapha National Park, north-eastward India. Biol. Cons. 141(5), 1429–1435 (2008).

-

Weckel, M., Giuliano, W. & Silver, Due south. Jaguar (Panthera onca) feeding ecology: Distribution of predator and prey through fourth dimension and space. J. Zool. 270(1), 25–xxx (2006).

-

Ramesh, T., Kalle, R., Sankar, Chiliad. & Qureshi, Q. Spatio-temporal partition among large carnivores in relation to major prey species in Western Ghats. J. Zool. 287(iv), 269–275 (2012).

-

Ramesh, T., Kalle, R., Sankar, K. & Qureshi, Q. Role of body size in activity budgets of mammals in the Western Ghats of India. J. Trop. Ecol. 32, 315–323 (2015).

-

Edwards, S. et al. Making the most of by-grab data: Assessing the feasibility of utilising non-target camera trap data for occupancy modelling of a large felid. Afr. J. Ecol. 56(4), 885–894 (2018).

-

Harmsen, B. J., Foster, R. J., Silverish, S., Ostro, 50. & Doncaster, C. P. Differential utilize of trails by woods mammals and the implications for photographic camera-trap studies: A case written report from Belize. Biotropica 42(1), 126–133 (2010).

-

Di Bitetti M. S., Paviolo A. J. & de Angelo C. D. Camera Trap Photographic Rates on Roads vs. Off Roads: Location Does Matter, Vol. 21, 37–46 (2014).

-

Blake, J. K. & Mosquera, D. Camera trapping on and off trails in lowland forest of eastern Ecuador: Does location matter?. Mastozool. Neotrop. 21(i), 17–26 (2014).

-

Cusack, J. J. et al. Random versus game trail-based camera trap placement strategy for monitoring terrestrial mammal communities. PLoS I 10(5), e0126373 (2015).

-

Kolowski, J. Chiliad. & Forrester, T. D. Camera trap placement and the potential for bias due to trails and other features. PLoS I 12(x), e0186679 (2017).

-

Srbek-Araujo, A. C. & Chiarello, A. G. Influence of camera-trap sampling design on mammal species capture rates and customs structures in southeastern Brazil. Biota. Neotrop. 13(2), 51–62 (2013).

-

Wearn, O. R., Rowcliffe, J. M., Carbone, C., Bernard, H. & Ewers, R. Chiliad. Assessing the status of wild felids in a highly-disturbed commercial forest reserve in Borneo and the implications for camera trap survey blueprint. PLoS 1 8(xi), e77598 (2013).

-

Sadhu, A. et al. Demography of a pocket-sized, isolated tiger population in a semi-arid region of western Bharat. BMC Zool. 2(one), one–13 (2017).

-

Sunquist, M. What is a tiger? Ecology and behavior. In Tigers of the World 19–33 (William Andrew Publishing, 2010).

-

Gotelli, Northward. J. & Colwell, R. K. Estimating species richness. Biol. Defined. Front. Meas. Assess. 12, 39–54 (2011).

-

Colwell, R. K., Mao, C. X. & Chang, J. Interpolating, extrapolating, and comparison incidence-based species accumulation curves. Ecology 85(10), 2717–2727 (2004).

-

Rovero, F. & Marshall, A. R. Photographic camera trapping photographic rate equally an index of density in forest ungulates. J. Appl. Ecol. 46(v), 1011–1017 (2009).

-

Jhala, Y. 5., Qureshi, Q., Nayak, A. Thou. Condition of tigers, copredators and prey in India, 2018. ISBN No. 81-85496-l-1 https://wii.gov.in/tiger_reports (National Tiger Conservation Authority, Authorities of India and Wild fauna Institute of India, 2020).

-

Nichols, J. D. et al. Multi-scale occupancy estimation and modelling using multiple detection methods. J. Appl. Ecol. 45(five), 1321–1329 (2008).

-

Hines J. E. PRESENCE three.1 Software to approximate patch occupancy and related parameters. http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/software/presence.html. (2006).

-

Meredith, M., & Ridout, M. Overview of the overlap package. R. Project. 1–9 (2014).

-

Rowcliffe M, Rowcliffe M. M. Package 'activeness'. Animal activity statistics R Parcel Version. i (2016).

-

Soberón, M. J. & Llorente, B. J. The use of species accumulation functions for the prediction of species richness. Conserv. Biol. vii(3), 480–488 (1993).

-

Broadley, M., Burton, A. C., Avgar, T. & Boutin, Southward. Density-dependent infinite utilize affects estimation of camera trap detection rates. Ecol. Evol. ix(24), 14031–14041 (2019).

-

Bunnell, F. L. & Gillingham, M. P. Foraging behavior: Dynamics of dining out. Bioenerget. Wild herbiv. 1, 53–79 (1985).

-

Mishra H. R. The ecology and behaviour of chital (Axis centrality) in the Regal Chitwan National Park, Nepal: with comparative studies of hog deer (Axis porcinus), sambar (Cervus unicolor) and barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak) (Doctoral dissertation, University of Edinburgh). 1982.

-

Raman, T. Due south. Factors influencing seasonal and monthly changes in the grouping size of chital or axis deer in southern India. J. Biosci. 22(2), 203–218 (1997).

-

Karanth, K. U. & Sunquist, 1000. E. Behavioral correlates of predation by tiger, leopard and dhole in Nagarhole National Park. India. J Zool. 250(two), 255–265 (2000).

-

Harmsen, B. J., Foster, R. J., Silver, Due south. C., Ostro, Fifty. East. & Doncaster, C. P. Spatial and temporal interactions of sympatric jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor) in a neotropical forest. J. Mammal. 90(3), 612–620 (2009).

-

Nichols, J. D., Karanth, K. U. & O'Connell, A. F. Science, conservation, and photographic camera traps. In Camera Traps in Animate being Environmental 45–56 (Springer, 2011).

Acknowledgements

Nosotros thank the National Tiger Conservation Dominance, Wild animals Institute of India, and Wood Department of Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve for necessary permission, support, and logistics. We would like to thank Sourabh Pundir, Akshay Jain, and Adarsh Kulkarni for profitable in data collection and GIS work. Nosotros are thankful to our field assistants for their difficult piece of work.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

G.Southward.T. and A.S. conceived the study, performed the computations, and drafted the article. A.South. and Y.V.J. assisted with the analysis and writing of the final manuscript. Y.Five.J. provided resource and supervised the piece of work. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Figure iii, where the P-value reported at the end of the figure is wrong, "P=0.001" and "P=0.45" at present reads: "P=0.07" and "P= 0.02".

Supplementary Data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, as long every bit you give advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other 3rd party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the cloth. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended utilise is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted utilize, you lot will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this commodity

Tanwar, K.Due south., Sadhu, A. & Jhala, Y.5. Photographic camera trap placement for evaluating species richness, affluence, and activity. Sci Rep 11, 23050 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02459-w

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02459-w

Comments

By submitting a annotate you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something calumniating or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it equally inappropriate.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-02459-w

Posted by: pyattsawn1947.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Make A Camera Trap Grid In Arcmap"

Post a Comment